Blog > Modern AI Means We're the First Generation That Won't Be Surprised When Crisis Hits

David Herse | February 22, 2026

Modern AI Means We Might the First Generation That Won’t Be Surprised When Crisis Hits

“We are on the brink of collapse.”

Every generation predicts it.

And eventually, some of them are right.

Civilisations rise, prosper, optimise. Then fracture, fall, rebuild. But it’s not just civilisations. Markets. Companies. Governments. Supply chains.

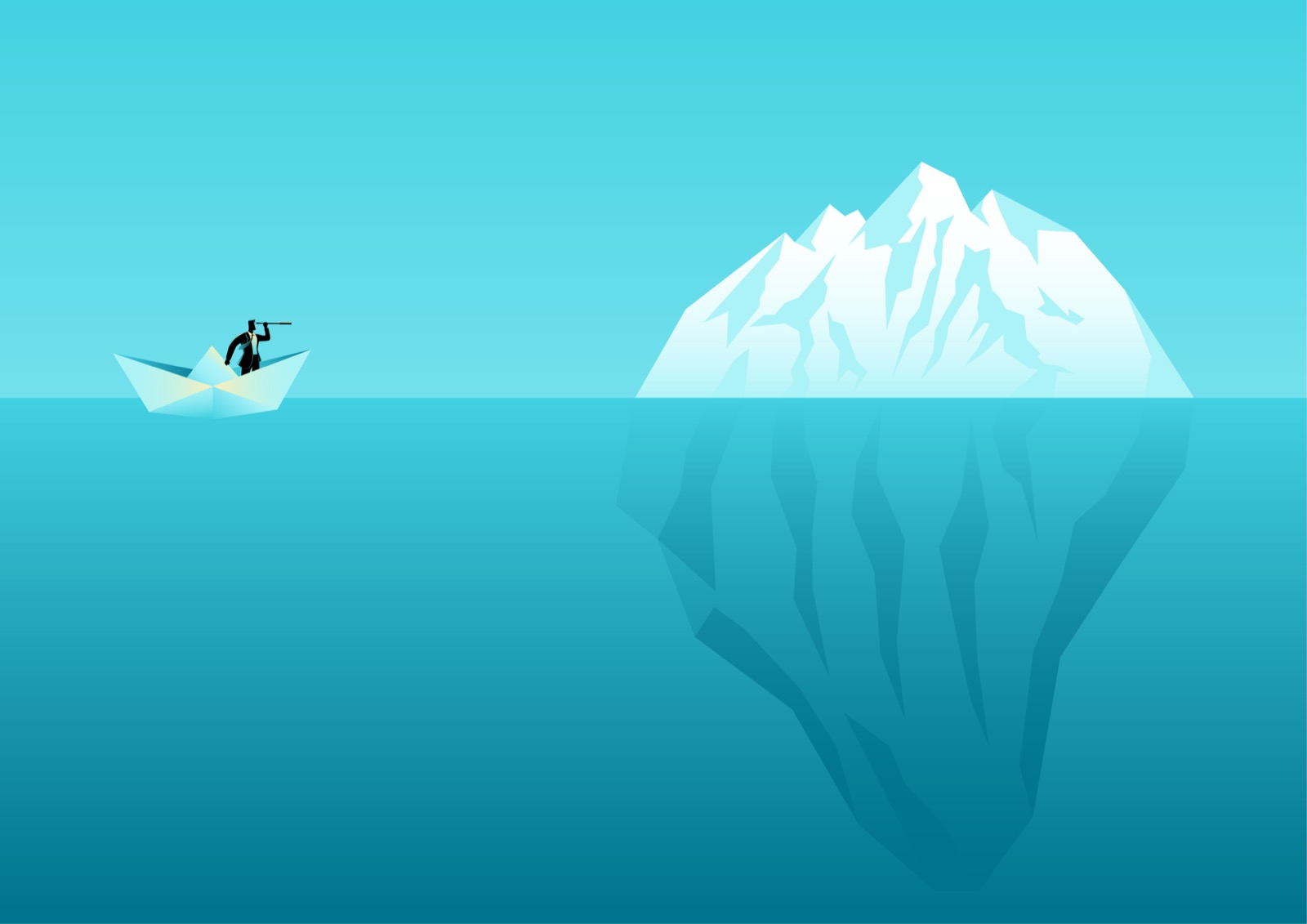

Collapse doesn’t come from a single shock. Not usually. It follows a pattern that’s almost boring in how consistent it is. Complexity outpaces adaptability. Power concentrates. Warning signs appear, and are rationalised away or ignored. Then a stress test arrives.

In 2008, it was financial contagion. A few over-leveraged mortgage securities, tightly coupled to everything else, turned into a global cascade. In 2020, global supply chains snapped. Hospitals overloaded. Ports stalled. One break became many, became everywhere. In February 2021, a winter storm hit Texas. Power plants failed. The grid operators watched failures cascade through power, telecom, data centres, and hospitals. By the time humans could diagnose what was happening, entire cities were dark. The damage was over $195 billion. The thing is, the warning signs were there for years.

In 2021, a single container ship, the Ever Given, wedged itself sideways in the Suez Canal for six days. And it disrupted an estimated $9.6 billion in trade per day, triggered shortages across Europe, and exposed how little slack we’d left in the system. Nobody designed fragility into the global supply chain. They just optimised it… until there was nothing left to absorb a shock.

Nobody designed fragility into the global supply chain. They just optimised it… until there was nothing left to absorb a shock.

At a smaller scale, it’s the same pattern. A traffic jam, bad weather, or a key person calling in sick can cause service to fail. Collapse isn’t malicious. It’s what tightly coupled complex systems do under stress. Especially when fragility is invisible or ignored.

Here’s what’s different now.

On December 30, 2019, a small AI platform called BlueDot noticed something odd. A cluster of unusual pneumonia cases near a market in Wuhan, China. The system had been scanning news articles in 65 languages, cross-referencing flight data, livestock reports, and climate patterns. It flagged the anomaly and sent alerts to its clients. Governments. Hospitals. Public health organisations.

That was nine days before the World Health Organisation issued its first public warning about COVID-19.

Nine days. In a pandemic, nine days are everything.

BlueDot wasn’t lucky. It was looking. It had built a system designed specifically to see what humans miss when they’re not watching everywhere at once. And when the signal appeared, buried in Chinese-language local news that most of the world would never read… it caught it.

This is the shift. Not that AI is smarter than us. It’s that it doesn’t get tired or distracted, and can read a hundred thousand news reports before breakfast.

Last year, a small London-based startup called Mantic entered its AI prediction engine into a Metaculus forecasting tournament, one of the most rigorous in the world. It placed 8th out of 500 human forecasters. Then they ran it again. It placed 4th. And more telling than the ranking: it beat the weighted average of all human forecasters combined. On questions about geopolitics, weather, box office results, Elon Musk’s Twitter behaviour. The AI wasn’t luckier. It was seeing more, and connecting it faster.

There’s even an AI model now purpose-built to predict Trump’s erratic behaviour. Not as a joke. As a serious forecasting exercise. Trained on 2,000-plus historical outcomes. Checks its predictions against what actually happened. The point isn’t Trump. The point is, if you can model that much complexity and unpredictability… you can model almost anything.

What’s different now isn’t that we’re wiser. And it’s not that we can design a perfect system, that idea is still a myth. What’s different is that for the first time in history, we have enough technology, data and computing power to see where systems are brittle before they break and to make more accurate prediction about what might happen next.

The Texas grid failure didn’t have to be a surprise. The Ever Given didn’t have to be a surprise. COVID didn’t have to catch us flat-footed. The signals were visible for those who were looking.

Anticipation used to be a privilege. Reserved for elites, specialists, those closest to power. Everyone else absorbed the shock. That’s what made past collapses so devastating, not just the collapse itself, but who saw it coming and who didn’t.

Anticipation used to be a privilege. Reserved for elites, specialists, those closest to power. Everyone else absorbed the shock.

That asymmetry is changing.

For the first time, that visibility isn’t reserved for institutions with the biggest research teams or hedge funds with the fastest models. It’s available to anyone who wants to ask the right questions and leverage the advancing technology in our hands.

Crisis may be inevitable. But surprise might no longer be.

And that changes the responsibility.